When Samuel L. Jackson took the stage at last weekend’s Super Bowl, he was — officially — a sidekick. His role, ostensibly, was to introduce Kendrick Lamar and provide a bit of interstitial commentary for the halftime show. Kendrick would go on to preside over a 13-minute funeral for a Canadian rapper (in women's flare jeans, no less), in front of all of America, with Serena Williams c-walking all over Drake’s grave.

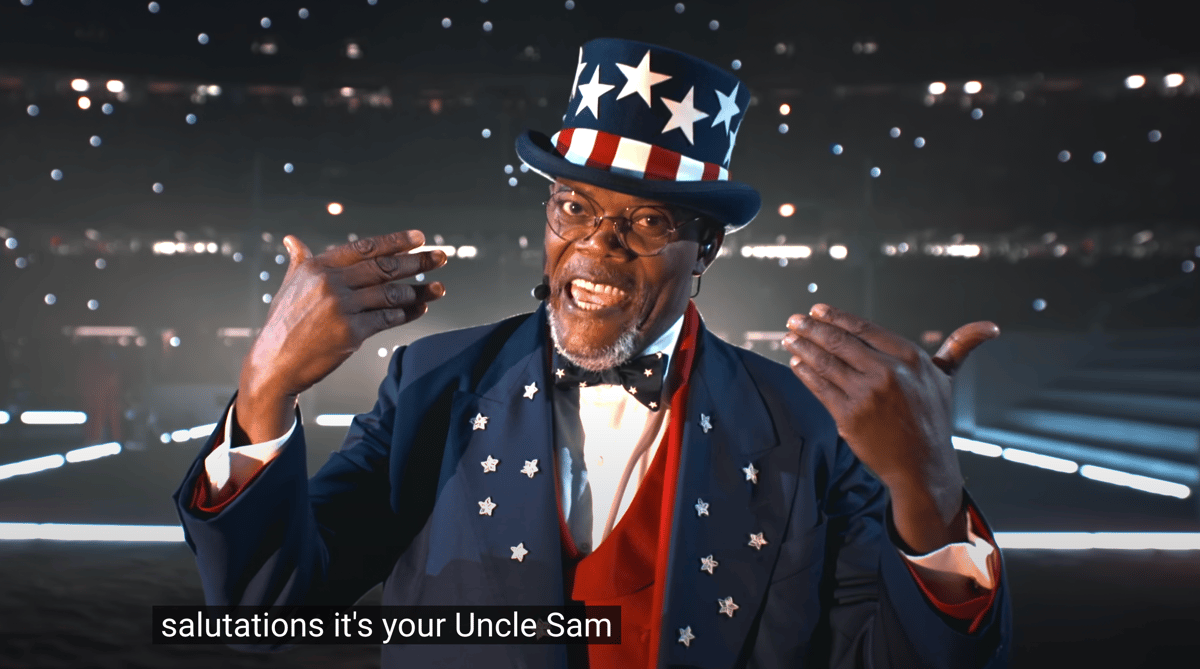

In a large top hat and custom Bode couture, Jackson kicked off halftime after Brad Pitt opened the game with a nod to national unity. After Lady Gaga serenaded the country on Bourbon St. After Taylor Swift and Donald Trump (who made presidential history by attending) arrived at the game to a mix of cheers and boos.

Samuel L. Jackson was a star situated in between several other humongo stars that night, there to introduce another big star who would go on to make fun of another big star. But my take is that he was the biggest of them all during the Super Bowl, and that his work on the field is perhaps the best representation of what America really means this Black History Month.

My entire life, I’ve felt a bit ambivalent about Black History Month. The way legends like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harriet Tubman were honored in school when I was growing up felt flat, trite, and infantilizing.

No one ever told me that Dr. King was also sometimes a bad student who almost flunked out of Spanish. No one ever told me that George Washington Carver was a cranky bisexual, on top of being obsessed with peanuts. There was so much I missed, because the whole month was made to feel like an after-school special.

To get back at the entire *world* for my miseducation, I played a game on this week’s episode of the show to honor great figures in Black History — in which I had writer-comedians Yassir Lester and Garrick Bernard join me in building a Black Hollywood Mt. Rushmore. You’ll have to watch or listen to see who made it, but know that I made a very strong case for putting Janet Jackson on that mountain top. (Her output is several times more interesting than Michael’s, and she could dance just as well as he did. Fight me.)

But I realized as soon as we wrapped the recording that Samuel L. Jackson, Mr. NFL Uncle Sam himself, should probably be on that great facade as well.

Samuel L. Jackson is the highest grossing movie actor of all time. Films he’s appeared in have made more than 7.42 billion dollars worldwide. Billion. Some of the biggest movie franchises of our era involve Samuel L. Jackson: Star Wars, the Marvel cinematic universe, Jurassic Park, The Incredibles. He’s also been a part of some of the most critically-acclaimed films of recent history, like Do The Right Thing, Django Unchained, Pulp Fiction, and Snakes On A Plane (a movie very good at being exactly the type of film it was trying to be, and should be considered a modern hetero-camp classic. Again, fight me.)

And so, to see the arguably world’s most famous Black man play the role he did on Sunday — it was beautifully subversive and transgressive and contradictory in all the right ways.

“Salutations. It’s your Uncle, Sam,” Jackson began, as he introduced Kendrick. “And this is the great American game.” Already, he’d challenged the status quo, by suggesting that America’s Uncle Sam could ever be anything but white.

He popped back up a few minutes into the halftime show with an admonition: “No, no, no, no,” he yelled to Kendrick. “Too loud. Too reckless. Too ghetto. Mr. Lamar, do you really know how to play the game? Then tighten up!” He’d turned himself from Black Uncle Sam to finger-wagging, race-policing Uncle Tom.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” Jackson said, after Lamar and SZA performed the optimistic, poppy Black Panther anthem “All The Stars.” “That’s what America wants. Nice and calm. You’re almost there.”

Samuel L. Jackson wasn’t just the MC of the show, he was also there to referee.

The performance represents the complex and maddening reality of being a Black creative in America, one that all the names I’d put on my Black Hollywood Mt. Rushmore have had to deal with. They are often asked to be Uncle Sams and Uncle Toms at the same time: keepers and makers of the culture, and often the ones asked to police it.

Who better than Samuel L. Jackson, one of the most successful actors of all time — someone who’s played both minstrel and savior several times over throughout his career — to lay this reality bare on the world’s biggest stage? Uncle Sam and Uncle Tom at the same time, sandwiched in between the world’s biggest stars, bigger than them all.

Author and activist Toni Cade Bambara once said, "The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.” I’ve always enjoyed this quote so much more than Gil Scott Heron’s “The revolution will not be televised.” For one, maybe it will be. But besides that, the word “irresistible” just contains so many more layers. What will be irresistible, exactly? And to whom?

Jackson’s halftime show performance shows that our desire for “revolution” — even the Black desire for it — can sometimes be just as irresistible as our own desire to police and restrain it. The hardest struggle may be internal, between these two competing impulses. Even if you make it to Mt. Rushmore.

With that, Happy Black History Month. Check out this week’s episode for more hot takes on Black celebrities we love. And in honor of Samuel L. Jackson, maybe watch Do The Right Thing this weekend. Or even Snakes On A Plane. I’m not kidding.

– Sam

Check out the latest episodes of The Sam Sanders Show here.