My Mom and Ruth Asawa

by Sharon Mizota

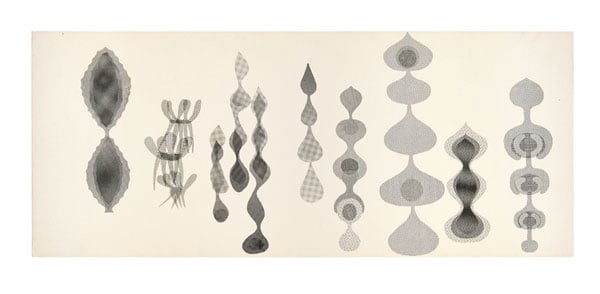

A 1950s-era print by the California-born Ruth Asawa shows her signature looped-wire forms. (James Paonessa / David Zwirner)

You may know Ruth Asawa from her elegant, abstract, hanging sculptures made of looped wire, which in recent years have become more visible and highly desired. (So desired that they have inspired knock-offs, as you may recall from this celebrity home décor controversy from 2022.) But Asawa’s world and her influence extend well beyond her famous globular pieces, as explored in a blockbuster retrospective of the artist’s work currently on view in San Francisco — an exhibition made more resonant by the artist’s personal history.

Last week, I visited my mom in the Bay Area to see Ruth Asawa: Retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the first posthumous retrospective dedicated to the Japanese American artist, who passed away in 2013.

My 84-year-old mother, despite using a walker, nearly sprinted through the first two galleries, which were dedicated mostly to the artist’s early drawings and paintings. She was probably eager to see the sculptures before her energy ran out, but perhaps there was some latent discomfort, too. These works were created in a moment not unlike our own, after Asawa was released from a concentration camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, one of 75 sites where people of Japanese descent (including my parents) were unjustly incarcerated during World War II. Like Asawa, my parents — who were held at Gila River, Arizona and Jerome, Arkansas — had seen their earliest years upended when the government forcibly removed them from the West Coast: homes lost, their parents’ professional lives destroyed, childhoods spent amid dusty barracks and barbed wire.

It was in these desolate confines that a teenage Asawa first took dedicated art lessons and decided to become an art teacher, ultimately enrolling in 1943 at Milwaukee State Teachers College. When she couldn’t secure a job due to anti-Japanese racism, she turned to Black Mountain College, an experimental art school in North Carolina. There, Asawa studied with German Modernist Josef Albers, architect Buckminster Fuller, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and other artists, exploring and exploding the boundaries between art and life. She also met her husband, architect Albert Lanier, with whom she eventually had six children.

Ruth Asawa making wire sculptures, 1954. (Nat Farbman / LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock)

The exhibition’s third room opened on a group of hanging wire sculptures, which finally got my mother to slow down. Especially lovely together, the silvery works undulate sensuously like jellyfish or mutating cells. Semi-transparent and swaying slightly in the wake of passing visitors, they create intricate and ever-changing intersections with each other and their own shadows, performing a slow, mysterious dance between solidity and air, tethered by gravity.

My mother was under the impression that Asawa had somehow knitted the wire, but we learned that she had been instructed in the looping technique by a teacher (whose name has been lost to time) in Toluca, Mexico, where she spent the summer of 1947 volunteering with the American Friends Service Committee. On view are several of Asawa’s early looped-wire efforts in more traditional forms: an oblong oval platter, a squat, bulbous basket.

Although the hanging sculptures are the big draw, and appear in myriad sizes, colors, and formal permutations, the exhibition underscores how they are just one facet of Asawa’s expansive and abiding practice. She drew continuously, made prints, and sculpted in clay, cast bronze, and dough, a material she explored in part to give her children something to do.

An installation view of the living room gallery in Ruth Asawa: Retrospective at SFMOMA. (Henrik Kam / David Zwirner)

At the heart of the show is a wood-paneled room meant to evoke Asawa’s San Francisco living room, which also served as her studio. Comfy chairs on a rug allow visitors to admire more wire sculptures hanging from the ceiling, a more intimate view that reveals how they list and twist internally, one hand-curled loop at a time. This room is also lined with art and domestic objects made or collected by Asawa, her family, and her many artist friends. Some are collaborations: a set of necklaces that looks like strings of pebbles turns out to be made of clay beads Asawa fashioned, then gave to her son, artist Paul Lanier, who pit-fired them at the beach.

The show is filled with such moments of quiet wonder: celebrations of nature, ingenuity, motherhood, community. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the galleries dedicated to Asawa’s public artworks. These are represented by mural-size photographs — which convey a sense of scale — alongside all manner of documentation shedding light on their inspirations and intentions.

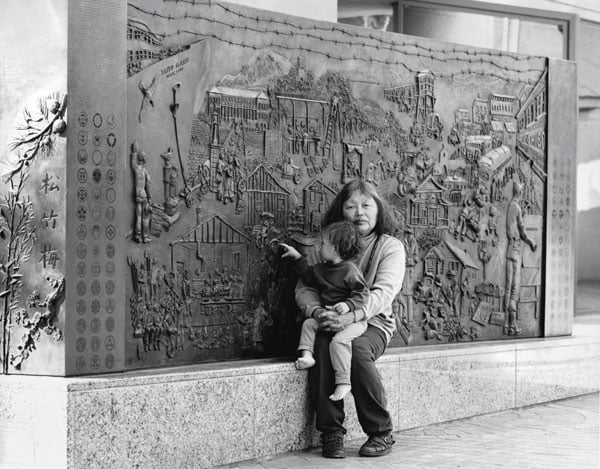

Mom and I spent the most time with “Japanese American Internment Memorial,” a bronze relief that Asawa created for San Jose’s Japantown in 1994. Our conversation focused not on its detailed depictions of immigration, forced removal, and the bleakness of camp life, but on the edges of the tableau, which are lined with mon, Japanese family crests.

Asawa and her granddaughter at the "Japanese American Internment Memorial" in San Jose. (Laurence Cuneo / David Zwirner)

Asawa sourced these emblems from her own family, friends, and the San Jose community, and my mom found one similar to her own. More than a nice design element, the mon personalize history: “This happened to our family.” They express bonds of kinship across generations, stretching all the way back to Japan. They emphasize continuity and steadiness.

For me, the unhealed trauma around incarceration continues to unfold, especially as U.S. history repeats itself in deportations, detentions, and other violations of civil and human rights (all of which rest on the same law that was used to detain Japanese Americans). But Asawa’s ability to condense and loop everyday moments and materials into objects of beauty, curiosity, and joy also reminds me what is possible in the wake of darkness.

➿➿➿

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective, is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through September 2nd; sfmoma.org.

Plus, KCET’s Artbound has an interesting doc on the Japanese American artists who emerged from World War II incarceration to shape U.S. culture.