EYE IN THE SKY

by Paula Mejía

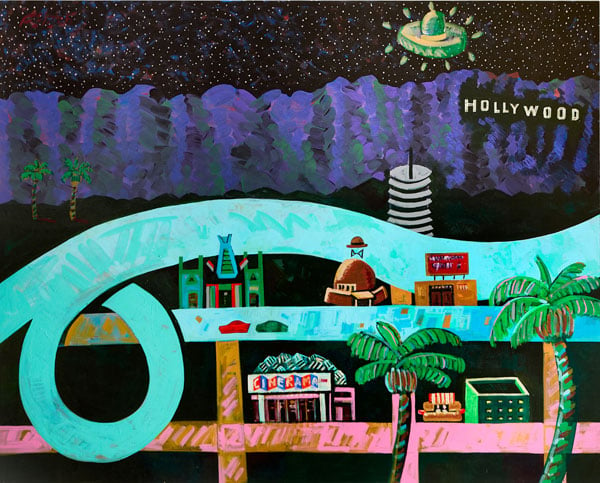

Frank Romero, Saucers Seen Over Hollywood, 2025. (Frank Romero / Luis De Jesus Los Angeles)

In Frank Romero’s six decades-plus of professional artmaking, the sweeping environs that distinguish LA from any other city in the world have become familiar visual motifs. Bushy palm trees and wending freeways spring up lavishly in his energetic paintings, as do icons of the city like the defunct Brown Derby. But to say that Romero’s hometown has acted as a muse — or a medium, even — doesn’t fully capture how consequential LA is within his vast body of work. Romero uses the city as a lens in his art, training it onto specific inflection points to pluck out themes of deep cultural and historical gravitas. As the last surviving member of the 1970s-era Chicano art collective Los Four, Romero, now 84, is himself a custodian of the region’s constant transfiguration.

A modestly-sized solo exhibition composed mostly of Romero’s newer works, now on view at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles in downtown, shows how Southern California continues to be a meaningful vessel for his expressive storytelling. California Dreaming features landscapes dusted with native plants and snapshots of a changed Hollywood — Romero’s take on the Golden State’s tantalizing pull that’s long drawn out-of-towners lurching for aspiration.

Frank Romero's paintings come off the wall in the form of painted sculpture — like this neon-illuminated car. (Frank Romero / Luis De Jesus Los Angeles)

Emblems of the cinematic golden years, which Romero was dazzled by as a child growing up in Boyle Heights, emerge in an intricate collection of cut-out pieces painted on wood, an homage to props used in these productions. In two outstanding pieces of neon art from 1992 arranged side by side, Romero fuses blinking light fixtures within the outlines of humming lowriders. One sees two silhouettes locked into a poster-perfect kiss, but the gaze is turned back on the viewer through the jarring flash of a paparazzi-style camera.

In this collection of paintings, neon art, and acrylic works on life-sized slices of wood, Romero makes a telling choice: In nearly every piece, he depicts the city not in its sun-dappled glory but rather in the throes of nightfall. The sole work that shows LA in the late afternoon haze, Flying Wing Over LA, from 2025, sees buildings casting shadows in downtown. It has an unsettling pall: Above the pink-paved streets and recognizable landmarks of City Hall, the Watts Towers, and Union Station, Romero has painted in bold strokes what appears to be a stealth bomber plane flying menacingly low, practically sweeping the tops of the neat palm trees above the Mission Revival train station.

Flying Wing Over LA, 2025. (Frank Romero / Luis De Jesus Los Angeles)

Elsewhere in the show, the subject of surveillance comes up again and again. In a sprawling piece depicting the 101 freeway as it curls through Hollywood, the Capitol Records building twinkling nearby, a flying saucer hovers in close reach — as though waiting for the opportune moment to strike. Even pieces set in other regions of the West see ideas of alienation and surveillance creeping into the frame: One piece, entitled Flying Saucer over Roswell, N.M., 2025, shows a car hauling a trailer behind it, a UFO nipping at its heels.

In the show’s press materials, Romero noted that these works were deliberately cheeky — a nod to the science fiction boom and extraterrestrial panic that gripped midcentury United States: “In the ‘50s, there was a phenomenon about flying saucers in the news,” Romero said in the statement. “I look back at that era with humor because I think it’s kind of funny.”

But viewed in 2025, on the heels of a fraught summer wherein federalized agents have arrested and deported thousands of residents on the grounds of them being “illegal aliens,” the pieces take on a different significance. For Romero, this recent art harkens “back to a time in my life when things seemed less serious, although at the time, I did not hear Eisenhower deporting Mexican nationals,” he added. “But really, though, the government has labeled the Mexican American this and others like us similarly before.”

Karla Diaz, La Causa (The Cause), 2023. (Karla Diaz / Luis De Jesus Los Angeles)

Another exhibition mounted simultaneously in the gallery — Karla Diaz’s Mal de Ojo — feels spiritually in conversation with Romero’s art, particularly where themes of surveillance are concerned. Named after the longstanding Latin American and Mediterranean superstition about a destruction-wielding malicious gaze, Diaz subverts the jealous stare through a series of self-portraits in her rapturous watercolor style, wherein the pigments bleed into one another to form a harmonious unit.

In them, she wonders what the malevolent eye might see if it were focused not on the individual but rather on the collective, a mechanism for shielding one another from harm. Some of her pieces are playful, such as one where she holds a tortilla up against her face, with holes poked out to reveal her eyes. Others are sobering, such as a sister portrait where she appears to stand in protest, her visage shielded by a piece of green papel picado. Although we can’t see her face, we can see her clearly through the shirt she’s wearing. In Spanish, it reads: “More poetry, less police.”

👽👁️👽

Frank Romero: California Dreaming and Karla Diaz: Mal de Ojo are on view at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles through Oct. 25; luisdejesus.com.