All is Full of Love

My encounters with art run the gamut. I’ve been delighted and impressed, stupefied and annoyed. I’ve seen exhibitions that take love as a theme, but rare is the display that leaves me feeling as if I’ve been embraced. Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal, which opened at the Hammer Museum earlier this month, is one of them — a show about an important jazz musician and spiritual leader that is also a moving meditation on love and grief.

This is not an easy concept for a museum to pull off. Coltrane has been a source of inspiration to visual artists, but was not a visual artist herself. And her primary acts of invention revolved not around physical objects, but acts that were more ephemeral in nature, be it the creation of music or the sustenance of devotional community. Nonetheless, the exhibition’s elegant installation design, along with the thoughtful curation by the Hammer’s Erin Christovale, make an engaging case for why Coltrane is a resonant figure across mediums.

Alice Coltrane playing the harp in 1970. (Chuck Stewart Photography / Fireball Entertainment Group)

Alice Coltrane was born Alice McLeod in 1937 in Detroit. To say she came from a musically-inclined family is an understatement: her mother played in a choir, her half-brother played bass, and her sister ultimately wrote songs for Motown acts. Alice would eventually become known as a jazz pianist, first in Detroit and, for a time, in Paris, where she befriended figures such as fellow pianist Bud Powell. Her first marriage to a scat singer was short-lived, but in her union with legendary tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, she found not just a husband, but a musical collaborator and spiritual colleague. (In the mid-1960s, the pair began to engage with Asian and African traditions.)

John’s sudden death in 1967 sparked a rupture for Alice, who channeled her grief into a deepened spiritual practice. She moved to California, took the name Turiyasangitananda, founded the Sai Anantam Ashram in a wild corner of Agoura Hills in honor of her guru Sathya Sai Baba, and even briefly hosted a public access TV show on KTTV that featured talks on spirituality, as well as prayer and chanting. Throughout, she put music in the service of faith — fusing divine Sanskrit mantras with groovy jazz and gospel. (See The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasantitananda from Luaka Bop.)

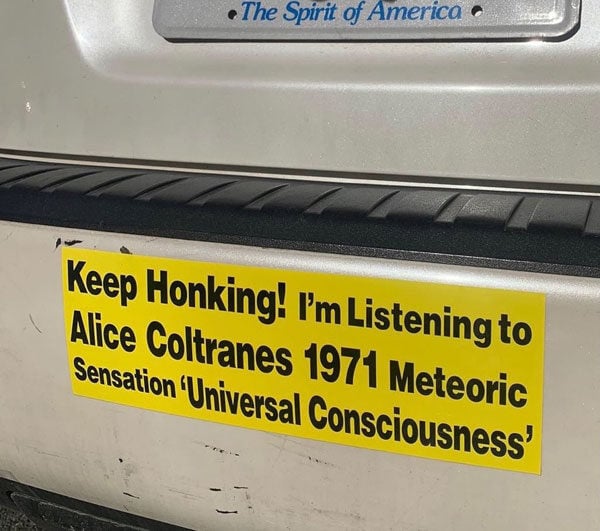

Since her death in 2007, Coltrane has attained a growing following among artists and music aficionados inspired by her singular path and her obliviousness to the boundaries of genre — among them, Steven Ellison, the producer and DJ known as Flying Lotus, who happens to be Coltrane’s grand-nephew (and whose work is included in the Hammer’s show). Coltrane, in fact, has even inspired a bumper sticker by LA artist Christopher DeLoach that reads: “Keep Honking! I’m Listening to Alice Coltrane’s 1971 Meteoric Sensation Universal Consciousness.” (GQ has a good story about its origins.)

The Alice Coltrane bumper sticker spotted in the wild. (Christopher DeLoach)

The Hammer’s exhibition features ephemera from Coltrane’s life: early photographs, a short doc from 1970, episodes of her public access show, as well as a pair of devotional paintings that she made to the deities Krishna and Rama sometime around 1980. But it fills in the gaps with work by 19 contemporary artists whose ideas are in dialogue with Coltrane.

A 2014 mixed-media wall sculpture by Rashid Johnson titled “Gotta Match” features the musician’s 1971 album Journey in Satchidananda on a small shelf at its center — taking on the feel of a devotional object. A short film by Ephraim Asili imagines Alice’s initial encounter with a harp that was gifted to her by John, but which didn’t arrive until after his death. "Isis and Osiris," as the piece is titled, features contemporary harpist Brandee Younger playing Coltrane’s instrument.

But I was especially thrilled to see Cauleen Smith’s wondrous 2017 video installation “Pilgrim” in the mix.

A still from Cauleen Smith's "Pilgrim." (Cauleen Smith / Morán Morán)

I first saw the piece in Smith's solo show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2021, and remember feeling as if I couldn’t peel away from it. The film combines dreamy footage of Coltrane’s Agoura Hills ashram with images taken at the Watts Towers and the Watervliet Shaker Historic District in New York State — sites that embody different aspects of generosity, community-building, and devotion. Serving as soundtrack is Coltrane’s stirring ‘70s era composition, “One for the Father,” dedicated to her late husband — which combines deep piano chords rooted in gospel with sequences that feature flights of feathery high notes.

At the Hammer, I again watched Smith’s piece as it played and then played again. It’s a poignant work, filled with love, but also colored by loss. The film is also a vital record: Coltrane’s ashram closed in 2017, and in 2018, the site was ravaged by the Woolsey Fire. As LA emerges from the devastation of the recent fires, in which the sting of loss remains heavy, this meditative show — about the care we show ourselves and those around us — is rich with empathy. In it, and each other, we find solace.

🎹🎹🎹

Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal is on view at the Hammer Museum through May 4th; hammer.ucla.edu.