The Good Earth

by Leigh-Ann Jackson

When I visited World Without End: The George Washington Carver Project at the California African American Museum (CAAM) for the first time, back in October, I thought I already knew plenty about Carver.

The D.C. classroom where I spent fifth and sixth grades was lined with portraits of historical Black luminaries. Carver’s mustachioed likeness hung above my seat, so every day I walked in to see him holding a test tube, surrounded by peanut plants. Born into slavery in Missouri sometime during the Civil War, Carver went on to become a prominent agricultural scientist who developed techniques for regenerating soil depleted by repeat plantings of cotton, and he used his findings to help support the work of independent Black farmers.

He was known as “The Peanut Man,” who’d discovered hundreds of uses for that legume, but my teacher made sure I also knew about his research on sweet potatoes and soybeans. When my niece enrolled at Tuskegee University, the historically Black college in Alabama, I learned more about his illustrious tenure at the school.

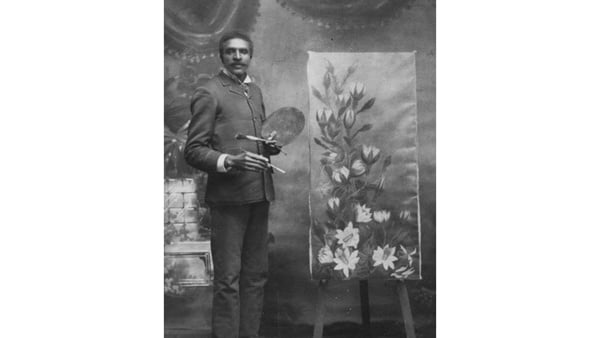

George Washington Carver at his easel in 1892. (Tuskegee University)

But CAAM’s exhibition, part of the Getty’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide initiative, showed me that I’d still only scraped the surface of the polymath’s genius. Co-curated by the museum’s executive director Cameron Shaw and independent curator Yael Lipschutz, World Without End displays an array of Carver’s groundbreaking inventions and archival materials, including a vial of Egyptian blue, the vivid pigment he created with oxidized Alabama clay, as well as a selection of Tuskegee Experiment Station Bulletins, in which he imparted wisdom about composting, nutrition, and home economics.

“Most people know Carver's name, but they have a limited or even erroneous view of his achievements,” says Shaw. “He was a pioneer of plant-based engineering. He was one of the nation's earliest public proponents of sustainable organic agriculture. He was seen as very eccentric in his time, but he really was operating at the forefront of conservationist thought.”

The show juxtaposes Carver’s artifacts with works by contemporary artists who echo his vision. Look at Kevin Beasley’s 2022 canvas, “Grace,” and you’ll see a beautiful painting of a tree. Look closer, and you’ll find that the canvas is made out of T-shirts made of raw Virginia cotton — honoring Carver’s commitment to reintroducing subsistence-first planting practices to Southern farmlands ravaged by capitalistic monocrop farming.

A work by Sam Shoemaker inspired by George Washington Carver's interest in fungus. (Leigh-Ann Jackson)

Elsewhere, Sam Shoemaker’s ceramics are an ode to Carver’s fascination with all things fungal. The beautifully grotesque sculptures — which are built around actual mushrooms and flank a cluster of spore specimens Carver discovered in the early 1900s — are so engrossing they might get you in trouble with museum security. It’s really hard not to lean in close!

But that desire to zoom in means you’re tapping into the essence of Carver’s lifelong obsession with nature’s nooks and crannies. Walking through the galleries, you learn that his attention to detail led him to find an intellectual spark everywhere — from roadside soil clumps to fallen leaves.

The show also highlights his skills as a resourceful artist who made paint by binding naturally-derived pigments with peanut oil and created charming landscapes on canvases made from materials like corn stalks. “So much of Carver's artwork was sadly destroyed in a fire at Tuskegee,” Shaw explains. “To be able to show the extant examples of his drawings and paintings was really special to us.”

CAAM is displaying some of George Washington Carver's few surviving paintings. (Elon Schoenholz)

Which brings me to the occasion of my second visit to the show in late January.

I was reeling from the devastation of the Eaton Fire, which had rocked neighborhoods just five miles away from my own. I’d been poring over social media posts boosting mutual aid efforts for Altadena’s historically Black community. I was heartbroken for close friends now facing the challenges of rebuilding.

This was all top of mind when I re-entered the show’s smaller gallery, anchored by Abigail DeVille’s fantastical reimagining of the Jesup Wagon, a school on wheels devised by Carver to share his methods with disadvantaged Southern farmers. The sculpture embodies themes of regeneration, grassroots community action, and environmental justice for underserved populations. It all felt very on the nose.

Abigail DeVille's "Jesup Blessup" at CAAM. (Carolina A. Miranda)

It’s heartening to know the spirit of his work endures — and not just within the confines of CAAM’s show. I’ve seen it in L.A.-based eco-activist Leah Thomas, whose International Environmentalist movement addresses such topics as food sovereignty and organic urban agriculture. Crenshaw Dairy Mart is also carrying the torch with Free the Land! Free the People! a study of the abolitionist pod, a multidisciplinary project emphasizing ecological sustainability and economic autonomy.

Carver laid the groundwork. It’s time to start sowing.

🌱🌱🌱

World Without End: The George Washington Carver Project is on view at CAAM through March 2; caamuseum.org.

Bonus: In March, the University of Chicago Press will release a new book by CAAM’s curators that examines Carver’s influence.

Double bonus: Crenshaw Dairy Mart is hosting a farmers market and a closing party for their current show on Feb. 15.