ART'S FIGHTING SPIRIT

by Paula Mejía

Radical Histories brings together work by 40 Chicano artists and collectives. (Linnéa Stephan / The Huntington)

Radical Histories brings together work by 40 Chicano artists and collectives. (Linnéa Stephan / The Huntington)

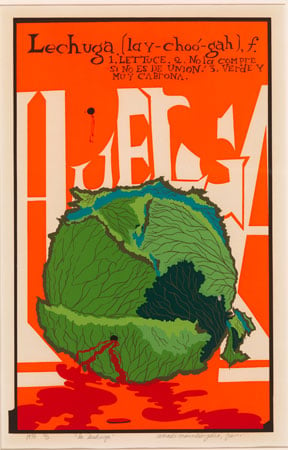

An emerald-green head of lettuce sits at the center of a bright orange print. Near the bottom, a small bullet has punctured its bulbous form, and it now oozes blood. Behind the lettuce, an abstract arrangement of letters spell out “HUELGA,” or “strike.” Right above the call to action, a dictionary definition offers three interpretations for the lettuce currently being exsanguinated — the most important of which urges the reader, “Do not buy it if it’s not union.”

Illustrated in 1974 by the Laredo-born artist Amado M. Peña Jr., this remarkable image was created amid the rising farmworker movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, when labor unions like the United Farm Workers (UFW) were calling for the boycott of nonunion vegetables and fruits amid fights for better working conditions. In the process, the “boycott grapes” protest signs that were toted along picket lines by workers, and even UFW cofounders César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, became icons. The many artists who sketched cartoon strips, palmcards, and fliers with bold pen strokes — like Peña Jr. — were among the forces who shaped the entwined lineages of Chicano protest and artmaking.

These artist-activists are the focal point of an expansive new exhibition at the Huntington Library in San Marino. Radical Histories: Chicano Prints from the Smithsonian American Art Museum gathers 60 pieces by Chicano artists and collectives from around the Southwest and beyond. Together, these document important socio-political movements, such as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, a coalition that organized marches against the Vietnam War around the U.S. (including one in LA in 1970 that ended in violence at the hands of Sheriff's deputies). The show simultaneously traces a people’s history of graphic artmaking — a history that finds itself in the crosshairs as the Trump administration attacks Smithsonian programming that he deems “improper.”

Amado M. Peña, Jr., La Lechuga, 1974. (Amado M. Peña, Jr.)

The show is divided into five sections. The first unpacks how the UFW, which used graphic prints to disseminate critical information about protests, inspired its own strain of art by showcasing explosive creativity through vivid colors, punchy slogans, and eye-catching icons. The UFW’s logo, a stylized version of an Aztec eagle rendered in black, figures heavily in the art of time, from placards urging people to boycott Delano Grapes to the flyers used to announce performances by El Teatro Campesino, a roving theater troupe connected to the farmworker movement.

But perhaps most significant is how these graphics were made. In one brightly-hued piece showing a proud farmworker reaching into a UFW bag, the wall label notes that these works relied on a network of volunteer artists working with donated materials at El Taller Gráfico, a printmaking center based in the Central Valley town of Keene. “To sustain the union and act as visual emissaries,” the text reads, “El Taller prioritized the rapid production of images, helping to mobilize communities across the country.” The text subtly underscores something poignant: although the movement created memorable fliers and slogans, the individual artists who lent their time to making that happen sometimes weren’t credited. The artist who designed this particular piece in 1975 — called I Am Somebody: Together We Are Strong — remains unidentified.

From there, the exhibition addresses how ensuing generations of artists have used printmaking to tackle everything from antiwar efforts to Chicano and Indigenous identity. In one image, a cartoon Richard Nixon smirks as a bomb fires off in the distance during the Vietnam War. Another from 1977, by artist Mario Torero, takes the familiar image of Che Guevara from the famed photo by Alberto Korda and mashes him up with Uncle Sam: he points back at the viewer and proclaims, “You are not a minority!!”

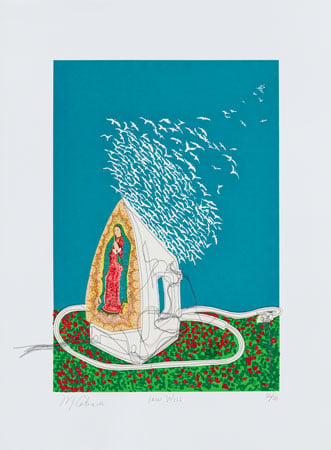

Themes of representation and identity likewise emerge in more recent work. A 2019 print by Ernesto Yerena Montejano celebrates Yalitza Aparicio Martínez, the first Indigenous Mexican actress nominated for a Best Actress Oscar. While a screenprint by Margarita Cabrera, titled Iron Will (2013), depicts an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on a clothes iron. It uses familiar iconography to comment on the invisible labor behind appliances, which are frequently mass-produced near the Mexican border. Hanging from the image are dozens of tiny threads.

Margarita Cabrera, Iron Will, 2013. (Margarita Cabrera)

Radical Histories remarkably brings printmaking right into our present moment. For its stop at the Huntington, the traveling exhibition includes an installation by LA muralist Melissa “Tochtli” Govea in conjunction with Self Help Graphics & Art, the longstanding Eastside print studio. Located at the end of the show, the installation meditates on the multi-generational lineage of Chicano artists working to sustain community solidarity.

The largest piece, a mural titled Sangre Indígena, incorporates dozens of photographs of Southern California-based artists and organizers with Indigenous roots. (Govea is of Nahua/Purépecha descent.) Also on display is a selection of her recent graphic prints. Govea pulls from various sources, riffing on Jenny Holzer’s famous aphorism, “abuse of power comes as no surprise,” as well as the Aztec eagle, and a tattoo-style artwork of a woman surrounded by butterflies. In the latter, Govea calls attention to the ICE raids currently roiling Southern California. “Ni una deportacion mas!,” it reads: “Not one more deportation!” In a smaller text, she added: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us!”

The federal government may try to suppress this activist history. But as this timely exhibition shows, political printmakers aren’t the sort to quietly back down.

✊✊🏽✊🏿

Radical Histories: Chicano Prints From the Smithsonian American Art Museum is on view at the Huntington through March 2nd; huntington.org.

.png?upscale=true&width=1200&upscale=true&name=email(600x100).png)