IS ANYBODY GOIN' TO SAN ANTONE?

by Leigh-Ann Jackson

Keenan Abercrombia ("Chef Kee") at the Compton Cowboy Ranch. (Compton Cowboys)

Growing up, my familiarity with Black folks in the Wild West basically amounted to watching Cowboy Curtis on Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and learning about Buffalo Soldiers in high school. (That’d be the 19th century Black servicemen who participated in military exploits like the Spanish American War). So I was eager to fill my knowledge gaps by visiting Black Cowboys: An American Story, which opened at the Autry Museum last month.

Organized by San Antonio’s Witte Museum, the show’s mission is to offer “a clearer picture of the Black West and a more diverse portrait of the American frontier.” Unfortunately, my visit left me wanting — even if I came away knowing more than before, and armed with a few solid leads on how to fortify that knowledge.

That’s because Black Cowboys is like walking through a Wikipedia page. The show is heavy on text — walls are lined with simplistic paragraphs about slavery, the cattle industry, and everyday life on the range, accompanied by reproductions of grainy archival photographs. Fabled figures such as legendary rodeo performer Bill Pickett and cowboy scribe Nat Love get VIP treatment. Meanwhile, a cluster of illuminated columns acknowledge lesser-known individuals, from formerly enslaved ranch workers to champion calf ropers.

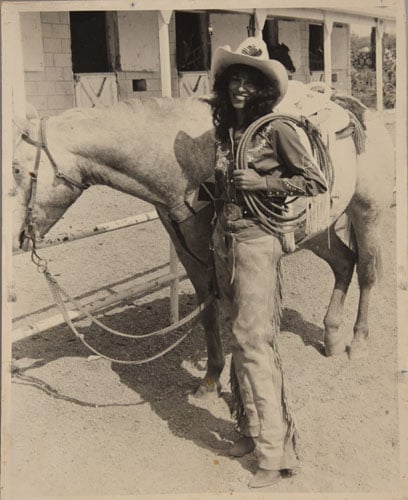

Sharon Braxton, a pioneering Black barrel racer, in Ontario, CA, 1983. (Courtesy of Michele Braxton-Nelson)

More physical artifacts would have enhanced the museum-going experience. But what you get is a pair of woolen chaps from the early 1900s; branding irons and a model of a six-shooter revolver here, an interactive replica of a chuck wagon and a pair of video installations there.

But the exhibition does fill a void at the museum. Downstairs in the permanent collection, there’s an installation chronicling the life of storied lawman Bass Reeves, one of the first Black deputy marshals in the US. Aside from that, there’s not a lot of real estate given to the experiences of Black folks, save for an alcove dedicated to Black pioneer communities that’s so dimly lit I needed my phone’s flashlight to see the photos and captions. (By comparison, the ongoing Imagined Wests, which explores the role of pop culture in the creation of Western myth, is more inclusive — and better lit!)

A 2011 Bill Pickett Rodeo trophy saddle. (Courtesy of DeBoraha Akin-Townson)

Curators at the Autry expanded on the original, more Texas-centric Black Cowboys exhibition with a wing focusing on Black trailblazers who shaped California. This includes displays about Los Pobladores, the Black and Afro Mestizo settlers who helped found the city of Los Angeles on behalf of the Mexican viceroyalty; Pío Pico, who served as the last governor of the area under Mexican rule; and, of course, the Buffalo Soldiers. Also included were modern-day keepers of the culture.

This half of the show packed the most punch, with the following additions piquing my curiosity the most:

L.A.’s contemporary cowboys ride out

Black Cowboys Community Profile, a video compiled by the Autry, bears out the enduring legacy of Black equestrianism in Southern California. In a series of one-on-ones, the founders and facilitators of groups like Urban Saddles and Compton Cowboys discuss their push to get young kids riding horses, learning time-honored skills, embracing nature, and flouting negative inner-city stereotypes. I also learned about the gone-too-soon community ranch, The Hill, and made a note to watch the 2020 documentary about it.

The LA Times also rounded up more ways to delve deeper into the South Central scene.

A still from the video Black Cowboys Community Profile. (Autry Museum)

The West’s Black women get their flowers

The flashiest item on display is a white horse mannequin donning a multi-colored hairpiece designed by cowgirl (and exhibition covergirl) Chanel Rhodes for her horse wig company, Mane Tresses. Yes, she sells synthetic tresses for riders who want their horses to slay the paddock sporting ombre manes and rainbow tails.

Rhodes’ My Little Pony LARPing showcases just one of many lanes occupied by Black cowgirls past and present. The show shouts out rodeo icons like barrel racers Sharon Braxton and DeBoraha Akin-Townson (their saddles are both on view), renowned Houston ranchers Mollie Taylor Stevenson, Sr. and Jr., as well as groundbreaking 19th-century horse-trainer Johanna “Chona” Phillips July Wilkes Lasley. Also included: landowning L.A. freedwoman Biddy Mason.

For more, see this LAist article, which gives a glimpse of the “We run this” mentality spurring on the next generation of Black cowgirls.

An installation view of Chanel Rhodes' barett and wig for horses. (Autry Museum)

Lights, camera, bad-ass cowpokes

Naturally, there’s a section devoted to the entertainment industry — because LA. In addition to props and costumes from early Black Western films, as well as Netflix’s more recent The Harder They Fall, there’s a small video screen commemorating 1970s cinematic offerings that fly in the (white male) face of Hollywood’s mainstream images of cowboys.

Watching the montage of movie clips inspired me to plan a backyard film fest where my guests and I watch Shaft star Richard Roundtree play a vengeful gunslinger in Charley One-Eye, munch popcorn while Blacksploitation beauty Vonetta McGee robs frontier banks in Thomasine & Bushrod, and root for Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee as they stick it to The Man on the dusty trail in Buck and the Preacher.

Film posters line a wall at the Autry. (Leigh-Ann Jackson)

🤠🤠🤠

Black Cowboys: An American Story is on view at the Autry Museum through Jan. 4th, 2026; theautry.org.

Plus, Carolina wrote about the diversity of cowboys for the New York Review of Books last year.